Posted on August 12, 2021

By Paul Vanguard, for BullionMax.com

We spend a lot of time talking about inflation, and how the dollar’s buying power slowly erodes over time. That’s a really hard concept for some people to grasp.

After the second consecutive month of 5%+ inflation, I feel compelled to revisit the topic, as it’s vital for every American to understand what’s actually at stake.

If I told you I knew someone, an average American named Willard, whose annual pay was $1,200 would you think he was comfortable? Do you imagine that’s enough to purchase food and shelter for himself, his wife, and three children?

Obviously not. That’s what the average American household spends on toiletries, booze and tobacco, vastly less than the $20,000 typically spent on housing.

Therein lies the mystery… How can Willard possibly consider himself comfortable? How can he cover his household expenses?

Welfare and food stamps, subsidized housing? Nope. No government handouts, no tricks.

Is he an heir, perhaps, who lives rent-free in a home full of servants with zero overhead expenses? Nope. Willard’s just an average guy.

How is this possible?

Unfortunately, only with a time machine. Willard is my great-grandfather. In 1913, he was a carpenter in Chicago, working 44 hours a week for $0.50 per hour. Every week, on payday, he walked home with four of these in his pocket:

Because he was a thrifty man, he saved a handful of those coins which he passed down through the generations until, ultimately, I received one. It looks like this:

Today, the average American household’s expenses are $60,000 per year. Prices generally have risen 28-fold since Willard’s day. There’s no way his $1,200 per year could pay today’s bills. Right?

Well, yes and no.

If you use the Bureau of Labor Statistics CPI inflation calculator, you’ll see Willard’s annual pay amounts to about $33,000 inflation-adjusted dollars per year. Definitely not enough to pay today’s bills. (In fact, just barely above the 2021 federal definition of poverty for a family of five.)

On the other hand, if his $40 weekly pay was still handed over in gold Indian-head coins? Based on today’s prices, the melt value alone would be $846 per coin, almost $3,400 per week… And an annual gross wage of $176,000.

That’s almost three times the typical family’s household bills. Over double the average family’s current income and comfortably in the top 20% of American incomes.

So now the question gets complicated: is $1,200 in 1913 dollars barely above subsistence level? Or is it much more? Is Willard’s family wealthy or not?

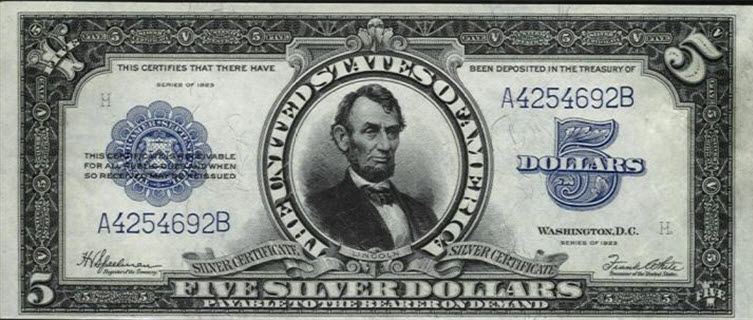

In Willard’s time, “money” was simple: gold and silver. Sometimes, paper, too, but that paper looked a little bit different…

1923 $5 bill source

Note the words on that piece of paper:

This certifies that there have been deposited in the treasury of The United States of America five silver dollars payable to the bearer on demand

Willard’s paper money quite simply represented physical metal on deposit. At any time, he could go to a bank and swap this bill for silver coins. This is what we’d today call a “fully backed currency.” This is primarily an issue of convenience (because nobody wants pounds of silver coins in their pockets), but consider that it requires trust as well (because nobody wants paper if they don’t believe those five silver dollars actually exist).

How different is that from today’s money?

Yuval Noah Harari, author and deep thinker, calls money a “collective fiction.” Here’s why:

Today, the total value of money worldwide is about $96 trillion. The amount of actual cash and coins in circulation is about $7 trillion. Some 90%+ of the money in the world exists only as a string of digits in a bank’s computer.

We know modern money doesn’t have intrinsic value, like Willard’s $5 gold coin. We know it doesn’t have full backing, like silver on deposit somewhere. So where does the value come from?

We’re far from Willard’s time. Today, the backing of a dollar comes mostly from the word of the U.S. government. After all, the government owns a LOT of property (about $6 trillion total as of 2020, including its gold reserves). But mostly, what the government has is the power to tax, and to make more dollars.

A dollar is, in a sense, a promise from the U.S. Treasury to the dollar’s owner that it has $1 in buying power. The form of the dollar doesn’t matter: it can be digital money in my bank, a crisp new $1 bill, four quarters or a hundred pennies. A dollar is a contract between the federal government and the recipient: “this thing has value and buying power equal to $1.”

The problem with that contract? It’s self-referential. You can’t define the value of a dollar as a dollar’s value. That’s nonsense.

Of the government’s two powers, the first, the power to tax, is politically difficult. No American votes for more taxes. No politician who raises taxes is likely to enjoy another term in office. And no career politician is ever going to get behind auctioning off government property. Raising these issues is political suicide (if not, a political “cry for help” perhaps).

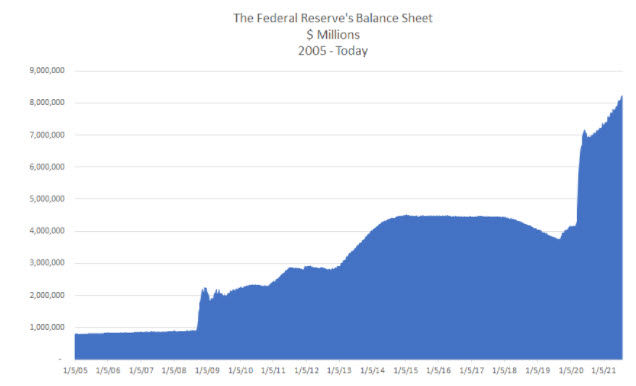

Making more dollars, though? That happens all the time. We call it Quantitative Easing, and it’s contributed about 8 trillion dollars to the total worldwide supply since 2005.

If we go back 20 years, we can see the purchasing power of dollars compared to other global currencies has dropped by 25%. This represents a certain amount of understandable skepticism from other nations that a dollar today will be worth just as much next month, or next year.

Why? If you take a look at the government’s balance sheet, you’ll see those $6 trillion assets are completely overshadowed by nearly $33 trillion liabilities.

For every dollar the government's got, there are $5.50 in claims against it.

That’s a recipe for disaster.

In comparison, in Willard’s time, the total government debt was $3 billion ($84 billion adjusted for inflation). That means U.S. national debt has increased about 400-fold.

Maybe you’re thinking, “That’s not such a big deal. After all, the government can just print more money, right?”

Ask the average person whether more money is better and they’ll always say, “Well, sure.”

Let’s do a thought experiment…

Let’s say Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates decide to join forces to fight poverty by doubling every American’s salary, just matching your paycheck out of their own personal petty cash. Next payday? Boom! Everyone has twice as much money to spend!

Now: is everyone twice as rich?

NO. Even though everyone’s spending money has doubled, what are they buying with it? The same amount of goods and services that were available before the sudden windfall. There is NOT a corresponding doubling of stuff available to buy.

And you remember what happens when more money chases the same amount of stuff? Prices go up. (That’s why the stock market is so outrageously overvalued right now -- there’s a whole bunch of stimmies chasing after the pre-pandemic amount of stocks. That makes prices rise.)

But wait -- there’s more!

When our uberbillionaire duo decide to double America’s salaries, that’s a transfer of wealth. Money flowed out of their enormous pockets and into ours.

On the other hand, when the Federal Reserve prints money, that means there’s more total money in circulation. That means we get a double whammy. Not only do prices go UP, but the buying power of every dollar in the world goes down.

New money dilutes the value of everyone’s dollars.

If the Federal Reserve decided to double everyone’s income… Well, once the euphoria wore off, things would get pretty ugly.

The rule of thumb here: price increases are directly correlated to the increase in money. Just like on eBay, when more people want something, the price rises. If all of America suddenly has twice as much cash, all of the prices Americans pay would double as well.

The overjoyed masses would run out to spend their doubled paychecks, only to find that their newfound wealth exactly matched price hikes.

So let’s never confuse some amount of dollars, whether it’s a million or a billion or a gazillion, with wealth. Like great-grandpa Willard once said, “Don’t matter how big a pile you got, if it’s a pile of crap.”

Willard and his family were happy (at least, according to the stories he told 6-year-old me). They always had food, shelter and clothing. Great-grandma Faye didn’t need to work. Instead she tended their back-yard garden when my grandpa, great-uncle Albert and great-aunt Myra weren’t causing a ruckus.

Willard provided for his family. He saw all three of his children educated, happily married, settled and gainfully employed. He saved enough money to enjoy a quiet retirement in the countryside and passed away in his sleep in 1987, 99 years old. He never made very much money, and he never had very much. He certainly wasn’t wealthy by financial measures.

He wasn’t what you’d call worldly, either. He’d seen incredible changes in the world over his lifetime, and a few of them he just didn’t trust.

Willard would never fly in an airplane. “If God wanted man to fly, he’d’ve give us wings.”

Willard didn’t trust electricity. When any appliance wasn’t in use, he carefully unplugged it and coiled its cord up neatly, “So the ‘lectric won’t run out.”

Willard didn’t like debt, IOUs or promises to pay. He never understood why the U.S. left the gold standard. A lifelong Republican, he would cuss Richard Nixon for thirty solid minutes if anyone happened to somehow raise the subject. He believed American life had gotten harder and harder since. He saw his grandchildren struggling to make ends meet, even on two incomes.

At the end of the day, great-grandpa Willard had learned some lessons. He successfully navigated almost a century of American economic booms and busts, from the Great Depression to Black Monday. He passed on his abhorrence of debt and distrust of faith-based assets. He spent his hard-earned money generously on things he valued like his children’s educations, home improvement, family vacations.

He always advised his family to spend their paper dollars on tangible things, mostly farmland and gold. Adjusted for inflation, farmland is up about threefold since he passed away in 1987. Gold’s price has risen more than fourfold.

Now, the great-grandpa Willard investment plan certainly isn’t for everyone! He was just a carpenter, after all, not a Wall Street Harvard MBA. I still think there’s something to be learned from his example: Stay out of debt, spend on what’s important, save what you can, invest in assets that don’t disappear when the lights go out.

Paul Vanguard is a lifelong precious metals enthusiast and a proud member of the BullionMax team.